By: Jason Mallard, Phillip Edwards, David Hall, Tyler Poythress, Sarah Beth Thompson, and Wesley Porter

Early season irrigation management can be a difficult management decision. Sporadic rainfall and unpredictable weather conditions make it difficult to know whether or not to irrigate. Too much irrigation early season on crops can cause shallow rooting systems, disease issues, and costly irrigation applications with no return. Rain predictions are hard to bank on, when part of the time it’s predicted to rain and it doesn’t and then when you decide it’s time to irrigate and the system has been running for a significant portion of the field and you get a shower that drops over two inches of rain.

While we have had a mix of dry weather and rain across the state we have had enough rain to put a majority of the state in the no drought classification. When we look at our crops however, we are at the point of requiring irrigation depending on crop, planting date and soil type. While driving across part of Georgia during the end of May, I saw a lot of pivots running both on corn and other smaller (probably cotton and peanut) crops. I know that we have been getting rain recently, but in some locations, it has not been enough and we are still pretty dry.

In certain areas of the State throughout last year we had somewhat limited rainfall events. However, when it did rain these events came with high intensity rainfall amounts. Similarly, one of the recent events in Eastern Georgia during early May was very similar with four plus inches in areas and was called an “atmospheric river” by Dr. Pam Knox. These larger events can cause issues with irrigation scheduling as most fields have a mix of soil types between sand and clay. While clay has a higher water holding capacity (SWHC) than most of our sandy soils, it has a lower infiltration rate. Heavy rain events often end with clay soils not absorbing as much while sandier soils can easily absorb more but have a much lower SWHC. Under these circumstances even though high amounts of rainfall were received it does not take long for the sandier portions of the field to require irrigation again while water is standing in the lower elevations. It is important to consider the type of soil in the majority of the field when determining when to trigger the first irrigation event after a major rainfall.

| Soil Texture | Infiltration Rate (in/hr) | Infiltration Rate (mm/hr) | Infiltration Class |

| Sand | 2.0-6.0 | 50-150 | Very Rapid |

| Loamy Sand | 1.0-2.0 | 25-50 | Rapid |

| Sandy Loam | 0.5-1.0 | 13-25 | Moderately Rapid |

| Loam | 0.3-0.5 | 8-13 | Moderate |

| Silt Loam | 0.2-0.4 | 5-10 | Moderate |

| Clay Loam | 0.1-0.3 | 2.5-8 | Slow |

| Silt Clay Loam | 0.05-0.2 | 1.3-5 | Very Slow |

| Clay/ Silty Clay | <0.05 | <1.3 | Extremely Slow |

It is important to remember that when you think about SWHC that 50% of the total SWHC is available to the plant. For example, even though a sandy soil may be able to store 1.0 inch of water per foot of soil depth (extraction only occurs where there are roots so consider rooting depth) only 50% of this is available to the crop. Thus, if you have a rooting depth of 1 foot, then 0.5 inches of moisture is plant available. The chart shows plant available water per foot of depth.

Available Water Capacity by Soil Texture (CLICK ARROW FOR DROP DOWN)

| Texture Class | Available Water Capacity (Inches/ Foot of Depth) |

| Coarse Sand | 0.25-0.75 |

| Fine Sand | 0.75-1.00 |

| Loamy Sand | 1.10-1.20 |

| Sandy Loam | 1.25-1.40 |

| Fine Sandy Loam | 1.50-2.00 |

| Silt Loam | 2.00-2.50 |

| Silty Clay Loam | 1.80-2.00 |

| Silty Clay | 1.50-1.70 |

| Clay | 1.20-1.50 |

Now you need to consider current water requirements of the crop. If the crop requires 0.15 inches per day at this stage, in three days you will have depleted 0.45 inches of moisture from the soil and will need to irrigate or replenish the soil moisture.

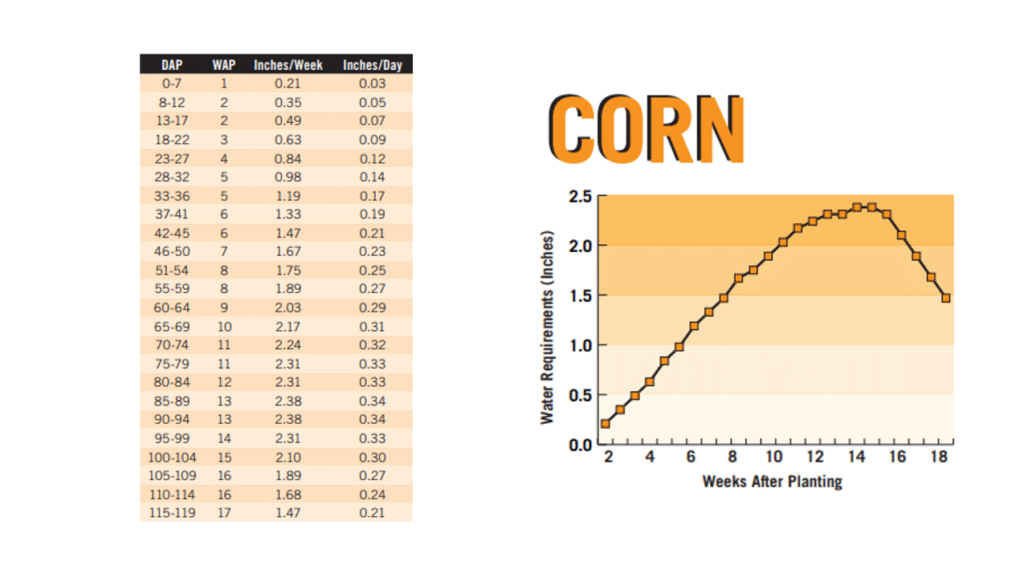

Corn

Most of the corn across southern Georgia is planted from late February (far SW) through early April (SE and N GA). Thus, corn is the crop that is the most mature and furthest along. Our corn is reaching the peak water requirement stage as it is moving into peak tassel. Now is the most critical time on our corn crop, we do not want to fall behind on water usage, as the high heat and drought that we have observed throughout the past few years in the month of June has led to pollination issues and reduced yields. Water usage on corn during the month of June into July can get as high as 2.5 inches per week when considering irrigation efficiency and current conditions. It can be difficult to keep up with this requirement if there is limited or no rainfall. This amount would require at least a 7 gallon per minute per acre pumping capacity. This is also assuming the system is running 24 hours per day 7 days per week. Thus, validating why during the months of June and into July that some irrigation systems do not shut off if there is no rainfall.

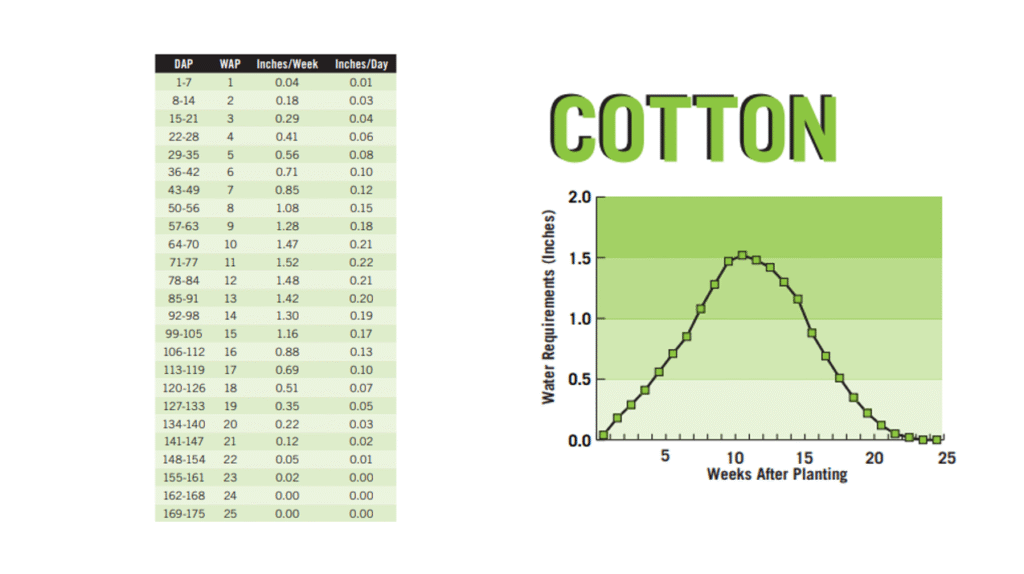

Cotton

Our cotton is typically planted between late April and early June. By the time this is posted most if not all of our cotton should be planted. Typically, early season water requirements for cotton are very low. Do not fall into the thought of allowing your soil moisture content to dry out in order for roots to develop deeper in search needed water. This is simply incorrect and for maximum yields, cotton should never be stressed from lack of moisture. Irrigation may be needed prior to planting to optimize planting conditions, or shortly after planting to activate herbicides if it has been dry and no rain is forecasted. After this point, conditions should be monitored regularly. Up to the first 30 days after planting, cotton requirement goes from 0.2” per week up to 0.5” per week. If you planted during mid-April, you are approaching near 1” per week. In all the comments referencing crops, the Checkbook method is our guide for this blog. It will keep you “between the ditches” and is used very often. The Checkbook method was created scientifically by using several factors averaging such historical data from ET rates, temperatures, crop needs per stage, etc. over a large period of time. Think about how often we have “average years” though. This point is being made because in times of low ET rates, days filled with cloudy and low-level rainfall allow for less water uptake than the Checkbook method would require and hot, low humidity, and sunny days will require higher replenishment than the Checkbook. This simple fact is where more advanced irrigation scheduling, such as moisture sensors, will supply real time data that will better inform you of times to lay off irrigation or to apply an application.

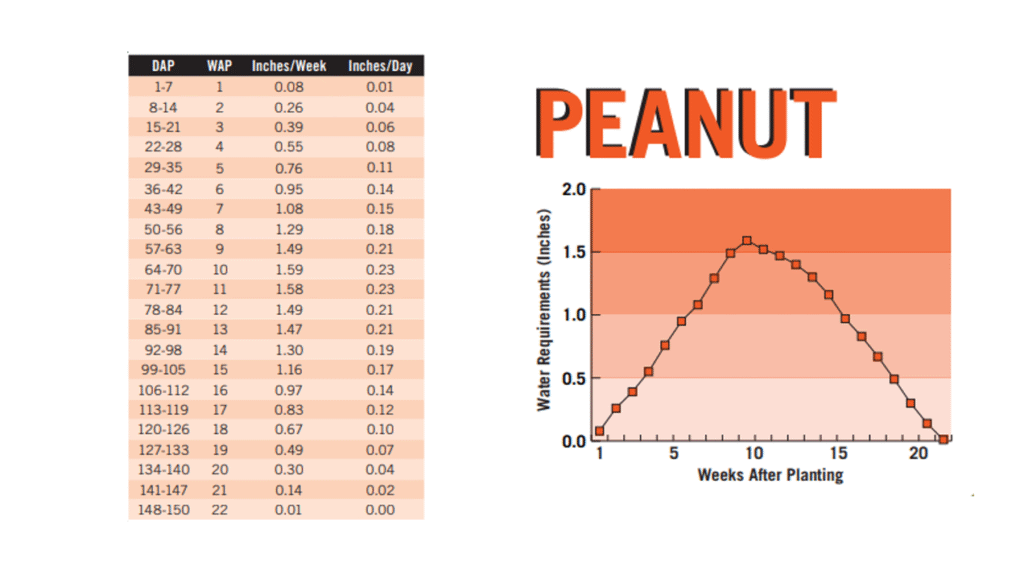

Peanut

Like cotton, peanuts should be planted from mid-April through early-June. Similarly, irrigation may be required for stand establishment and herbicide activation. After this point, soil moisture and weather conditions should be monitored closely. Typically, farmers don’t like to irrigate peanuts much in the first 40 days after planting, and while water usage during this period is very low, it does get up to an inch per week at the 40 DAP mark. As mentioned earlier the weather has been sporadic and will continue to be so throughout the month of June. Stay on top of early season water requirements to prevent crop stress early during the season. As peanuts reach the age of fungicide and herbicide applications, try and plan irrigation events around such activities. Most herbicide and fungicide applications require water to activate the chemicals once they are applied.

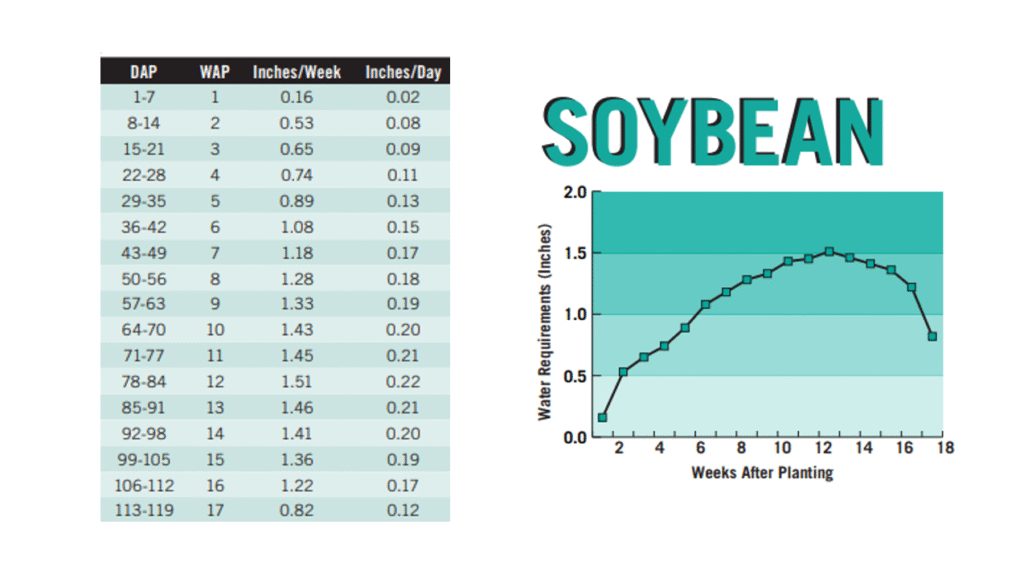

Soybean

Optimal planting windows for soybeans are similar to that of cotton and peanuts, thus, can be competing for irrigation at the same time. The irrigation requirements are similar to those of cotton and peanuts too. However, early during the season, soybeans require higher amounts of water more rapidly than cotton and peanuts. Depending on when the soybeans were planted, irrigation may be necessary earlier in the season than it would be for cotton and peanuts. Thus, it is more critical that you don’t fall behind during the beginning of the season on soybeans. They are more sensitive during the early vegetative stages and flowering to drought stress than cotton or peanuts. Whether your soybeans are determinate or indeterminate, the checkbook method mentioned should keep you “between the ditches” but soil moisture sensors will be more accurate and help you predict the lack of moisture before soybeans suffer potential yield loss.